Endurance

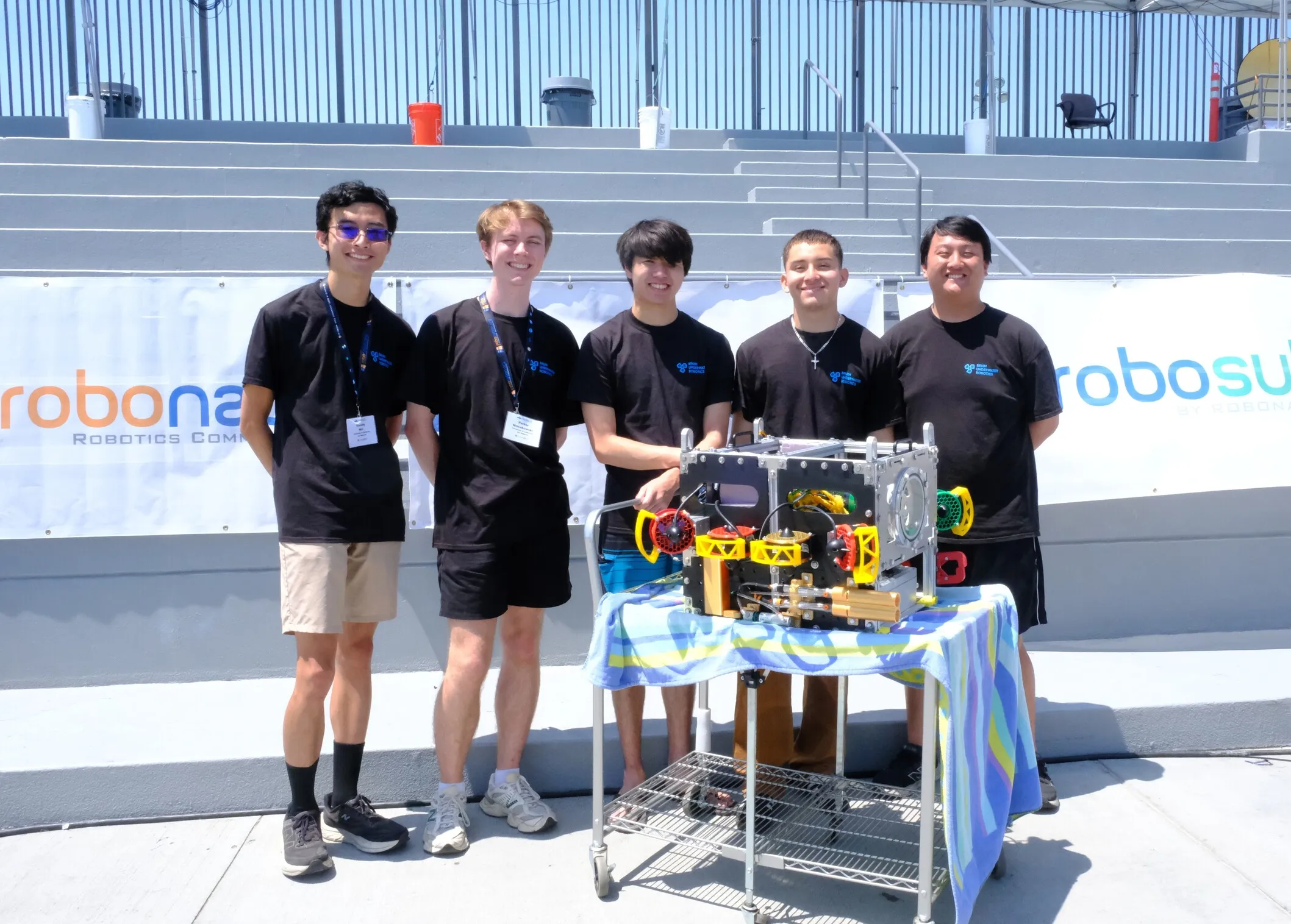

The 2024-2025 season marks Bruin Underwater Robotics (BUR)’s second year competing in Robosub, as well as designing autonomous robots in general. Our goal for this year was to use the lessons we learned in our rookie year to create Endurance, a more robust vehicle.

Much effort has been taken to reprioritize and narrow the scope of our competition goals. As such, we have decided to focus on the core features needed for autonomous behavior, with navigation and localization being our main goals for this season. To fulfill these goals we have implemented a simple, yet modular, design for our AUV. We have made this decision for the hopes of utilizing the same vehicle for systems and controls testing for future seasons. This, along with development of a virtual simulation platform, will allow us to perform systems-level testing while designing future AUVs.

Much effort has been taken to reprioritize and narrow the scope of our competition goals. As such, we have decided to focus on the core features needed for autonomous behavior, with navigation and localization being our main goals for this season. To fulfill these goals we have implemented a simple, yet modular, design for our AUV. We have made this decision for the hopes of utilizing the same vehicle for systems and controls testing for future seasons. This, along with development of a virtual simulation platform, will allow us to perform systems-level testing while designing future AUVs.

Robosub 2025!

Subsystems

Mechanical: Chassis

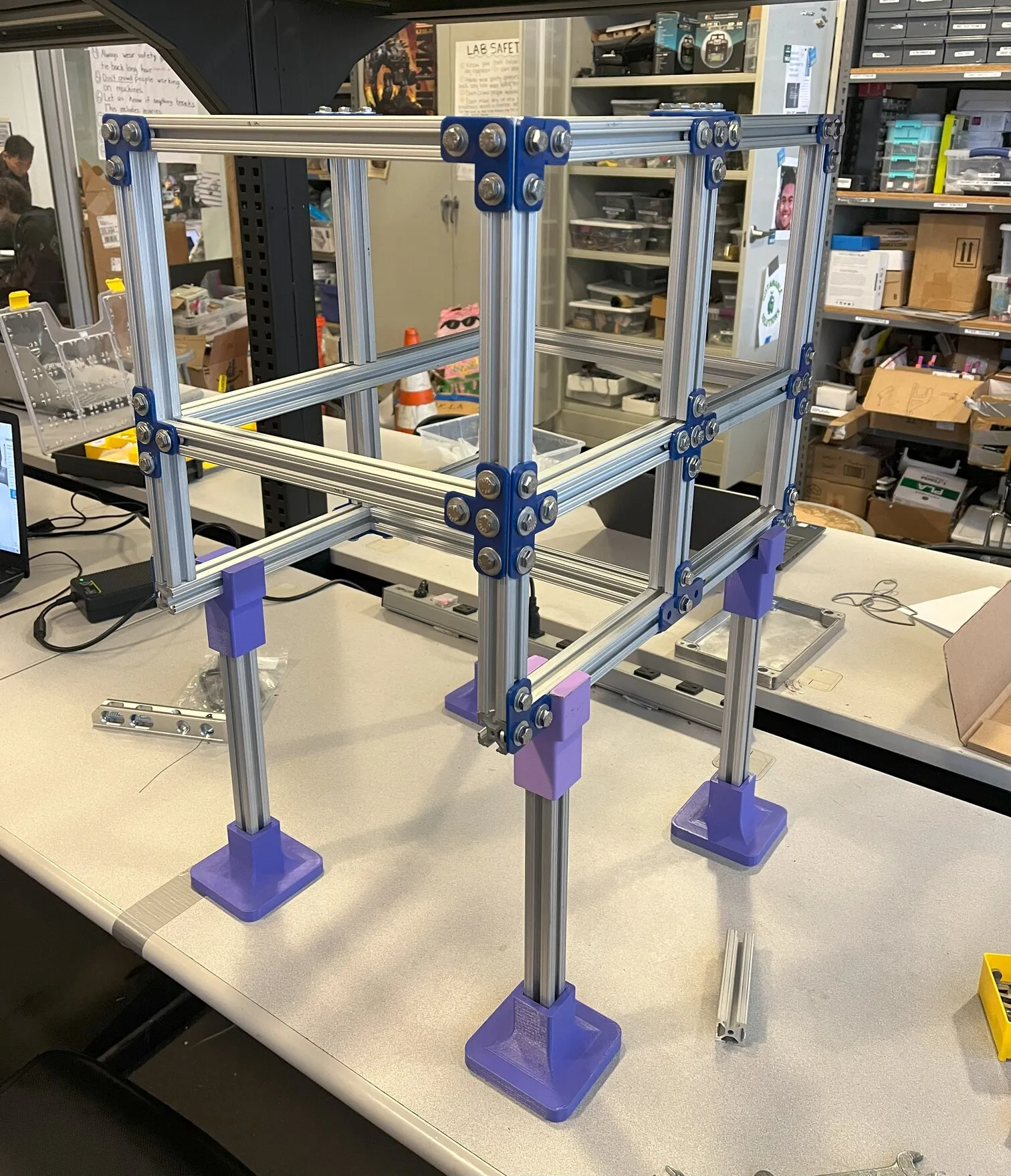

The main priorities when designing the chassis of our autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) for this year’s competition were durability and optimization. While competing last year in our debut into RoboSub, our team ran into unforeseen issues with our AUV being hard to maintain and set up during competition. Another motivator was lifespan: we wanted to make sure our robot could last for several years, allowing us to always have a testing platform for robot software.

That experience influenced us to go for a simpler, sturdier, more reliable design this year. Compared to our previous design, which had to use hinges to fold/unfold during assembly and reassembly, our new robot features significantly less moving parts. This reduces the amount of stress placed on our parts during normal operation. Another change was in materials -- we built our entire robot frame out of aluminum profile extrusion to ensure durability.

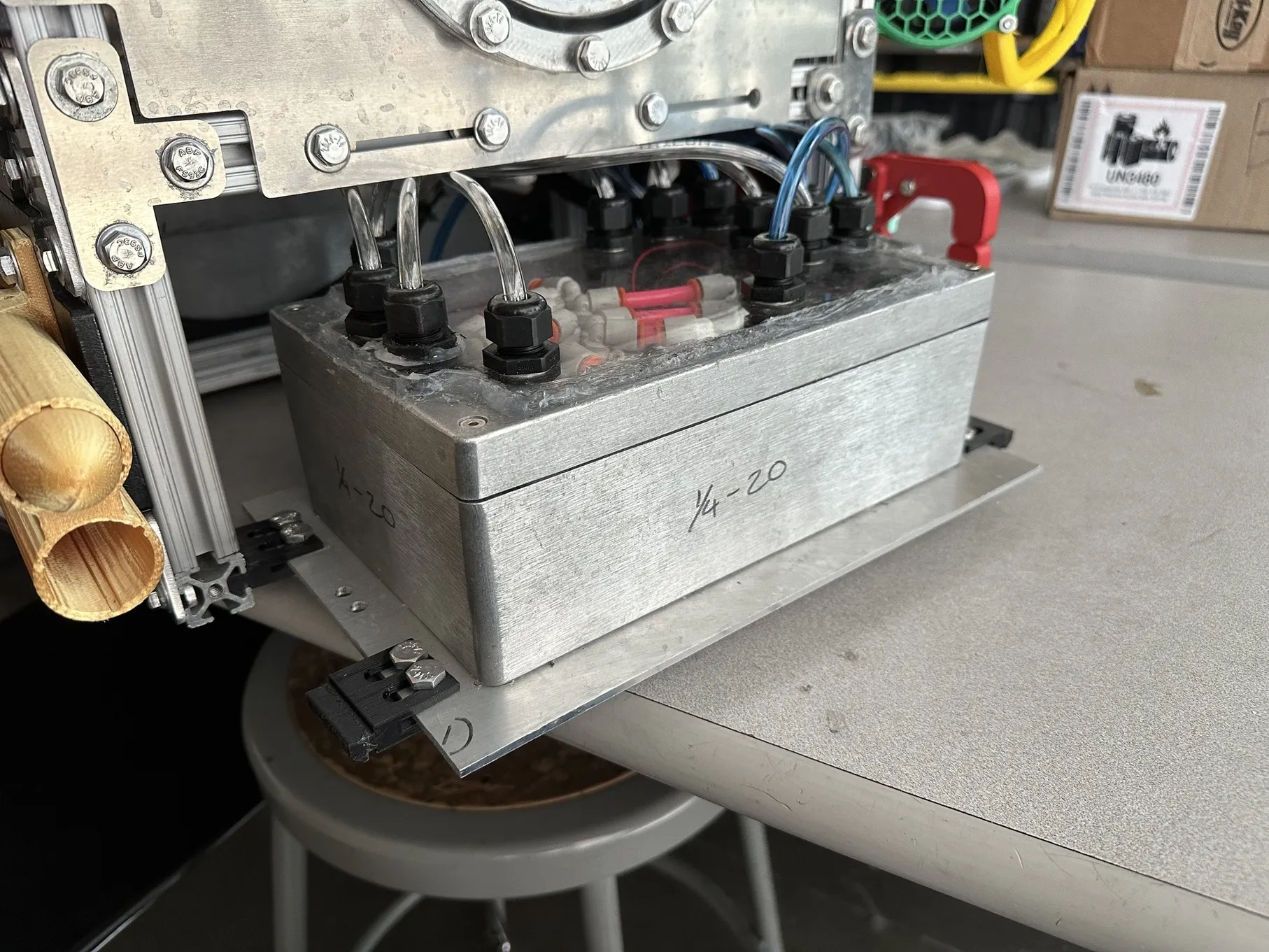

Another goal we had was to make the robot easier to take apart and rebuild if necessary. Our previous design required a lengthy disassembly and reassembly even to make simple changes. Not only did this take a lot of time, it was also a safety risk: the more we took apart the robot, the greater the likelihood of a mistake occurring during the reassembly process, potentially resulting in catastrophic damage. (Our previous robot suffered a catastrophic leak during Robosub 2024 semifinals due to an improperly-sealed O-ring, which spurred this new design direction.) To that end, our simpler design has significantly cut down on the time needed to make changes to the robot. Another minor feature: slide-out panels to hold the boxes that hold our pneumatics and batteries allow easy access to these parts, while still allowing us to keep a slim profile.

That experience influenced us to go for a simpler, sturdier, more reliable design this year. Compared to our previous design, which had to use hinges to fold/unfold during assembly and reassembly, our new robot features significantly less moving parts. This reduces the amount of stress placed on our parts during normal operation. Another change was in materials -- we built our entire robot frame out of aluminum profile extrusion to ensure durability.

Another goal we had was to make the robot easier to take apart and rebuild if necessary. Our previous design required a lengthy disassembly and reassembly even to make simple changes. Not only did this take a lot of time, it was also a safety risk: the more we took apart the robot, the greater the likelihood of a mistake occurring during the reassembly process, potentially resulting in catastrophic damage. (Our previous robot suffered a catastrophic leak during Robosub 2024 semifinals due to an improperly-sealed O-ring, which spurred this new design direction.) To that end, our simpler design has significantly cut down on the time needed to make changes to the robot. Another minor feature: slide-out panels to hold the boxes that hold our pneumatics and batteries allow easy access to these parts, while still allowing us to keep a slim profile.

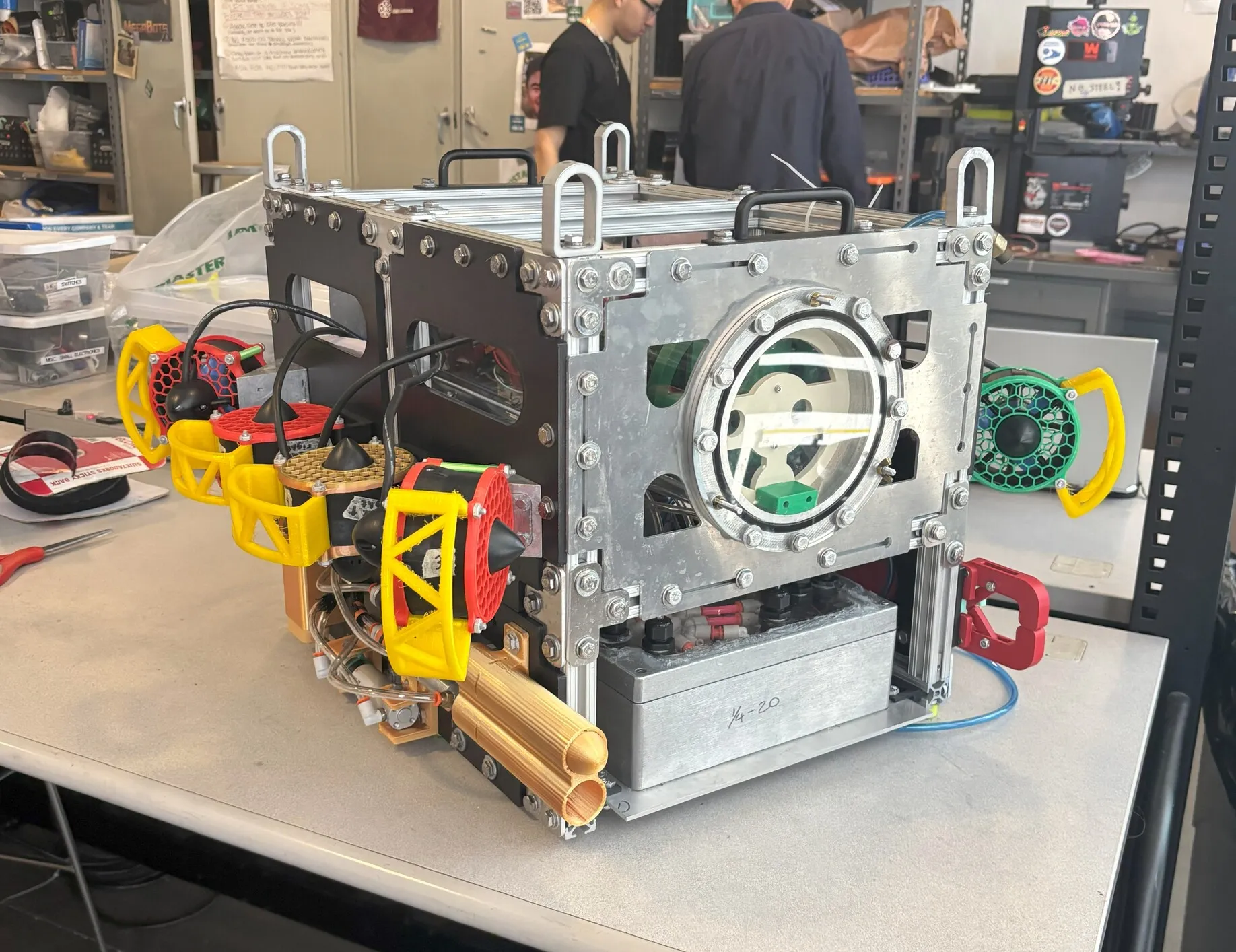

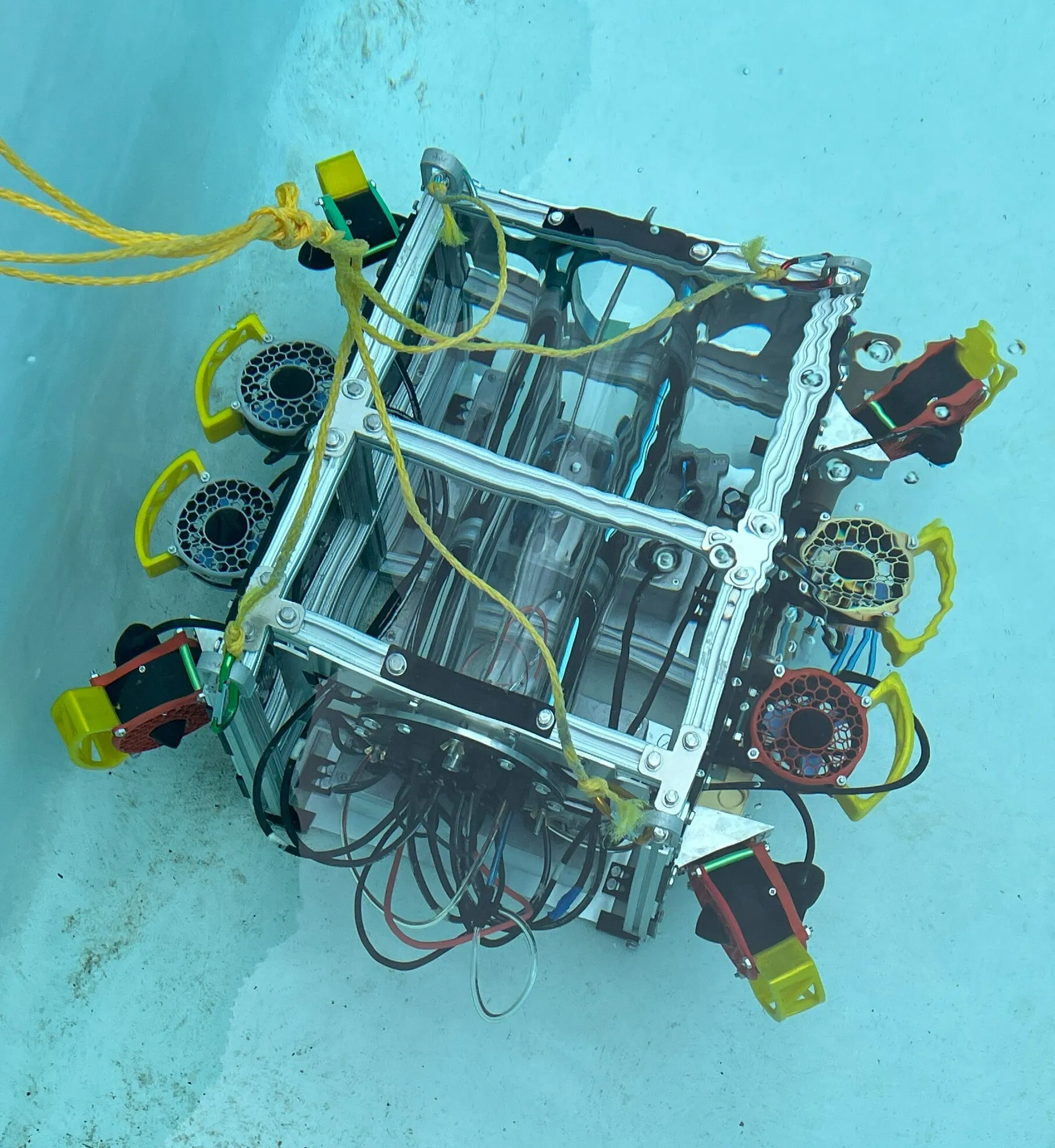

Endurance's Aluminum Frame

Slide-Out Pneumatics Box Panel

Mechanical: Dive-Ops

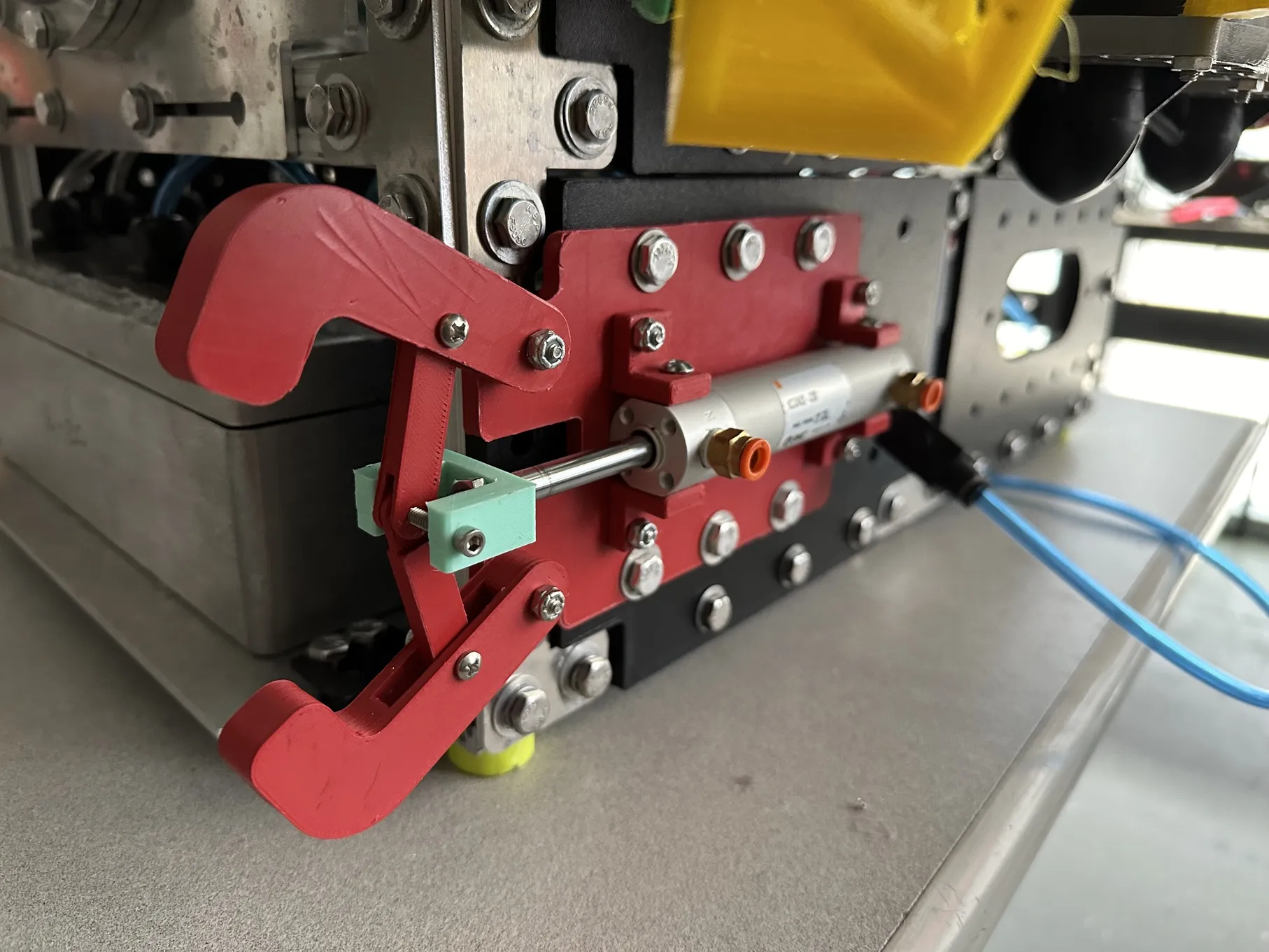

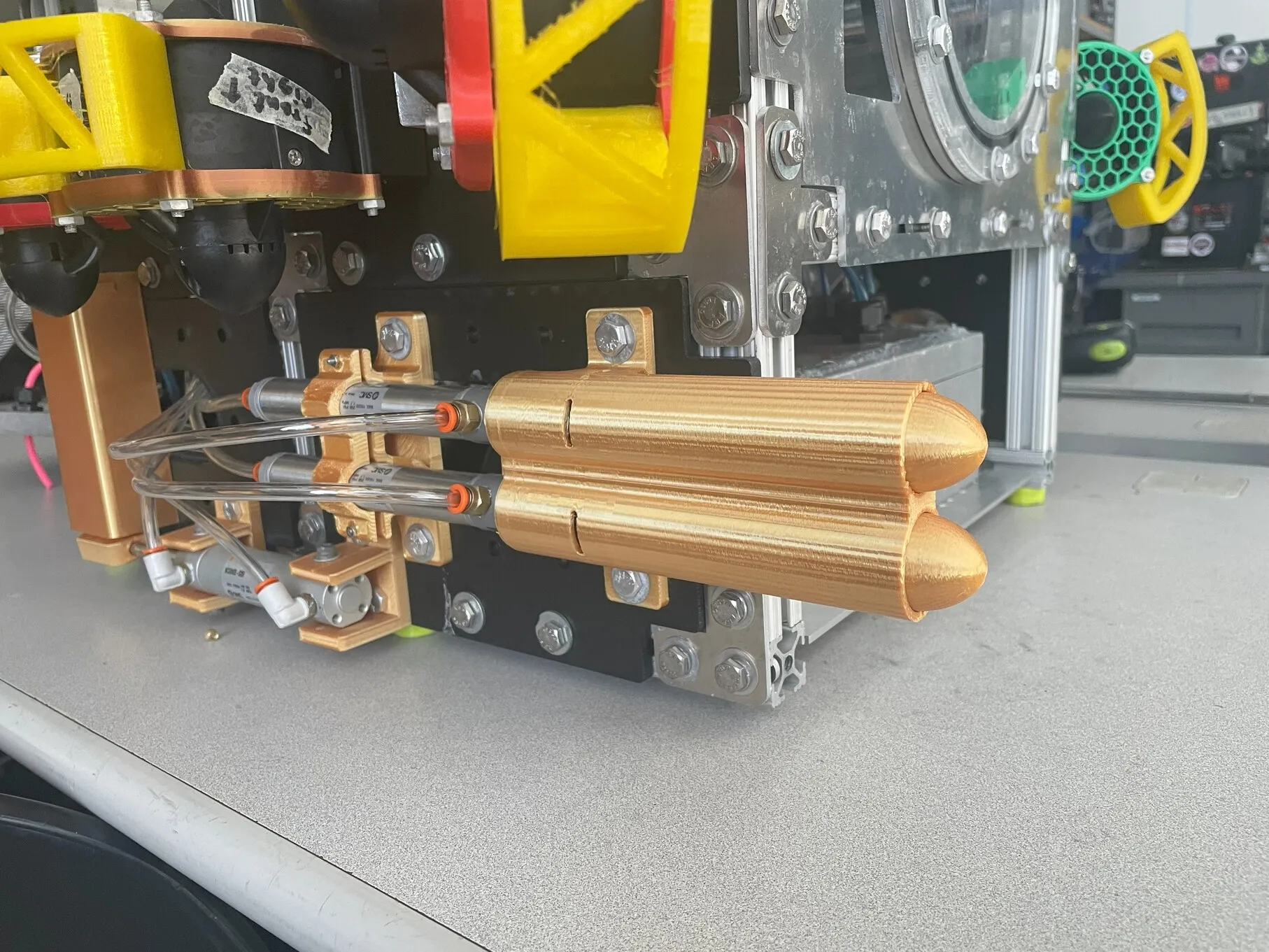

Similar to last year, this year we decided to use pneumatics to operate our three main end-effctors: our torpedoes, arm, and dropper. Our system consists of a paintball air tank connected to four solenoid valves that control the flow of air to the 4 actuators. To ensure that the system was safe, we used a vented ball valve, 2 relief valves, and a pressure regulator to ensure the operating pressure was kept below the maximum pressure rating of the individual components.

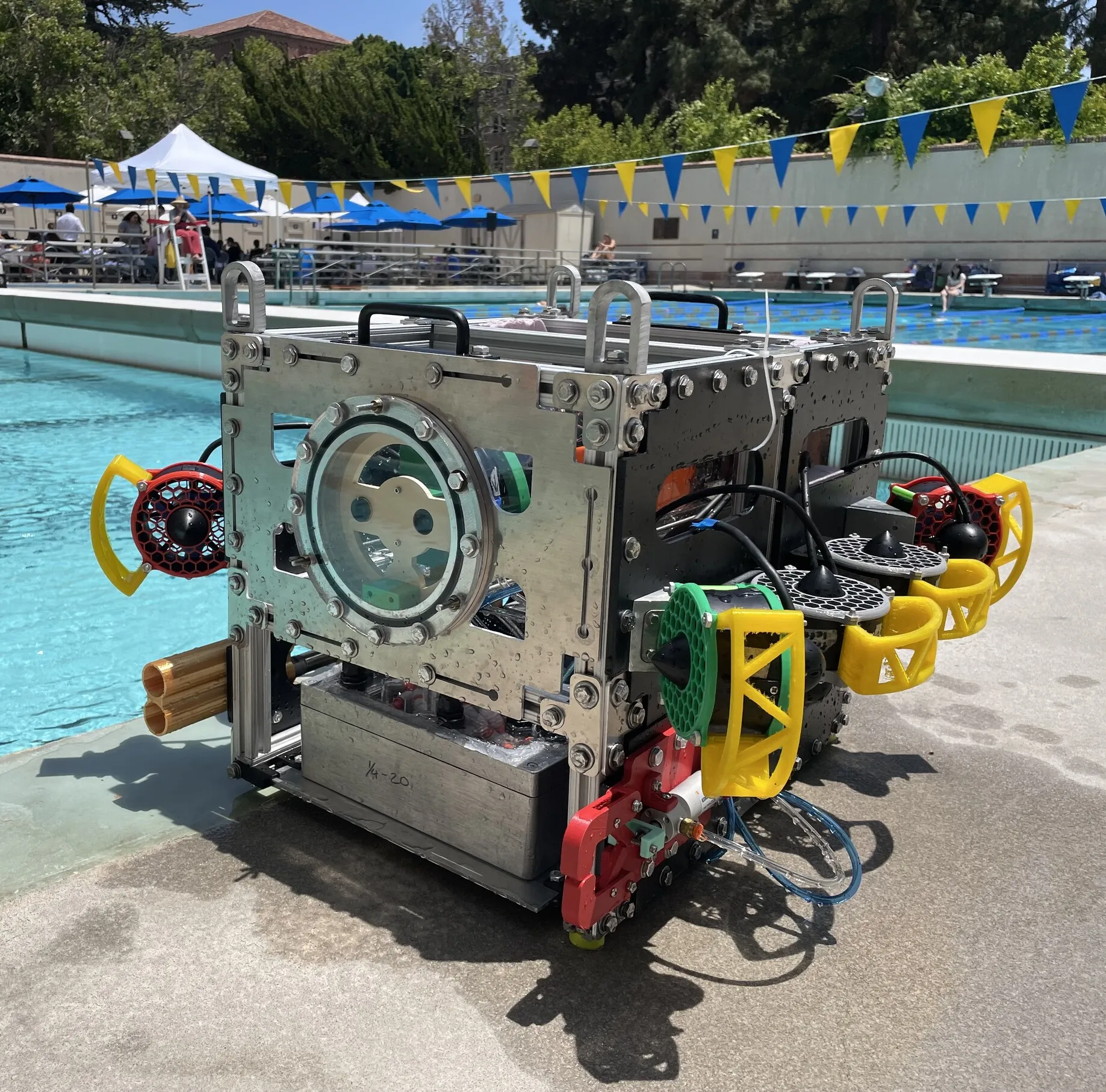

Arm

Dropper (Back) & Torpedoes (Right)

Electronics: Hardware

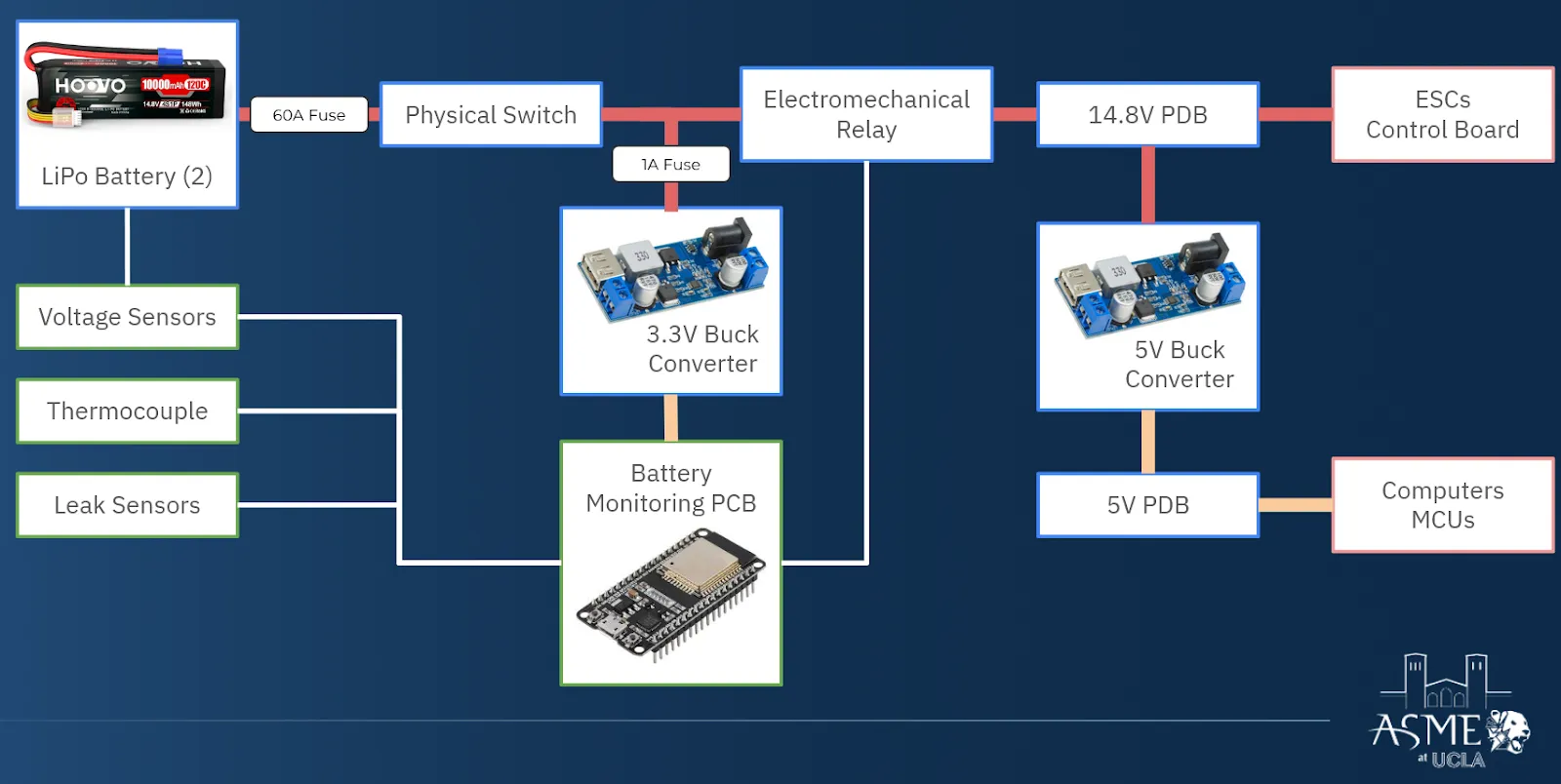

Most of the overall structure of our AUV's electronics were retained from our last year's robot. The most significant change lay in our battery-monitoring board, which monitors the voltage of each cell and will automatically cut power if any abnormalities (overcurrent, undervoltage, leak detected via an attached sensor, etc.) are detected. This year, we redesigned the board to rely on a physical relay and power MOSFET to draw power from the main batteries directly, rather than a dedicated 11V battery. This change results in a simpler and easier-to-modify electronics system compared to previously.

System Power Diagram

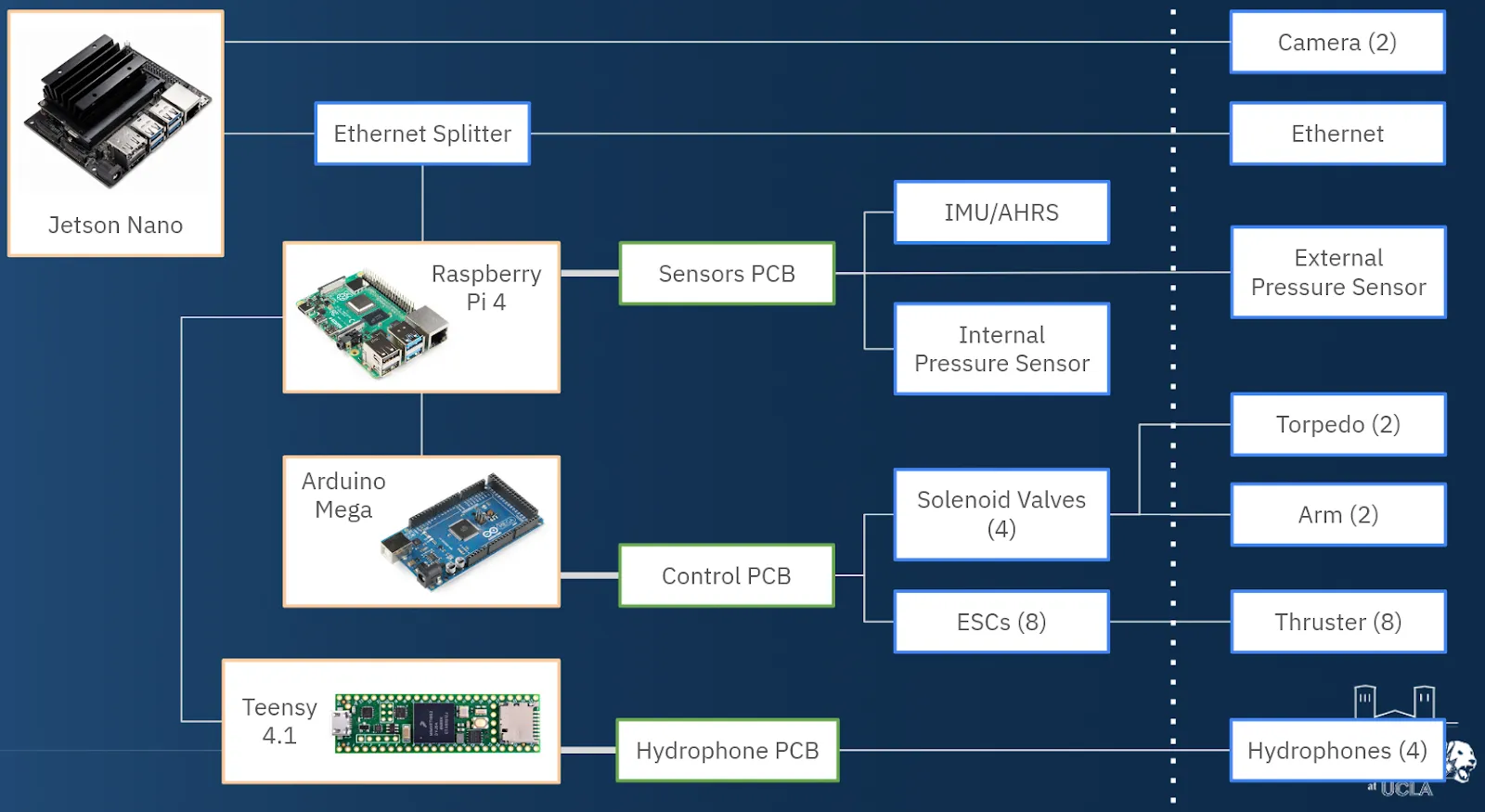

Electronics Functional Block Diagram

Electronics: Software

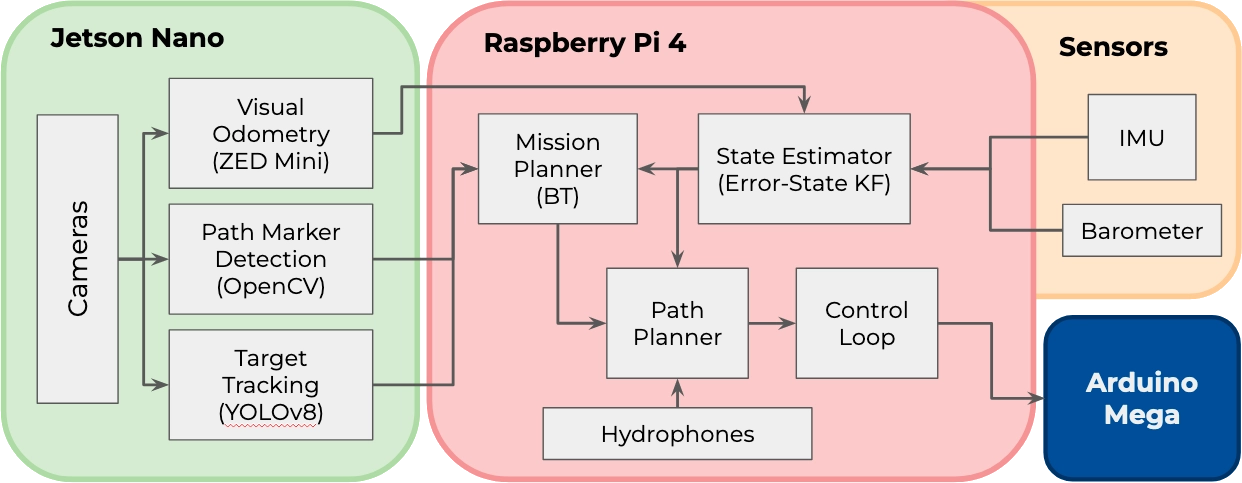

Software Subsystem Diagram

Similar to our electronics, much of our onboard software stack remains unchanged from last year. One big push, however, came in our offline processing capabilities. This year, we put a major focus on using simulation for robot testing and vision training. Historically, our software teams had often had limited time to test software, as our manufacturing processes typically did not finish the robot until over halfway through the year. With simulation, our goal was to be able to test software anytime -- a major long-term benefit for our project, if it could be achieved.

For physical simulation of the robot (e.g. for testing controls and motion), we used the Gazebo Garden simulation suite with its Hydrodynamics plugin to simulate underwater dynamics. Gazebo was chosen due to its significant ROS integration, which allowed us to effectively drop in our existing software stack and immediately test it (with only minimal changes for testing). Although we were not able to finish our simulation component in time to use it before real-life pool tests began, we intend to use it going forward, and are excited for the long-term possibilities that simulation might open up for our software team in the future.

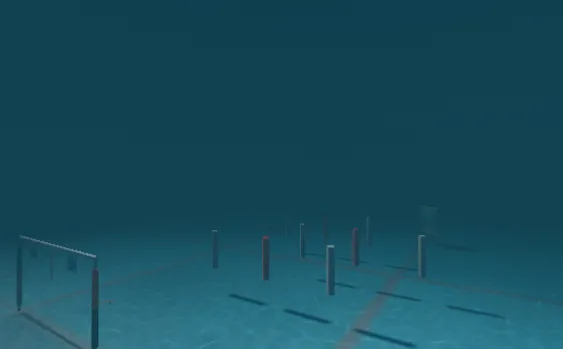

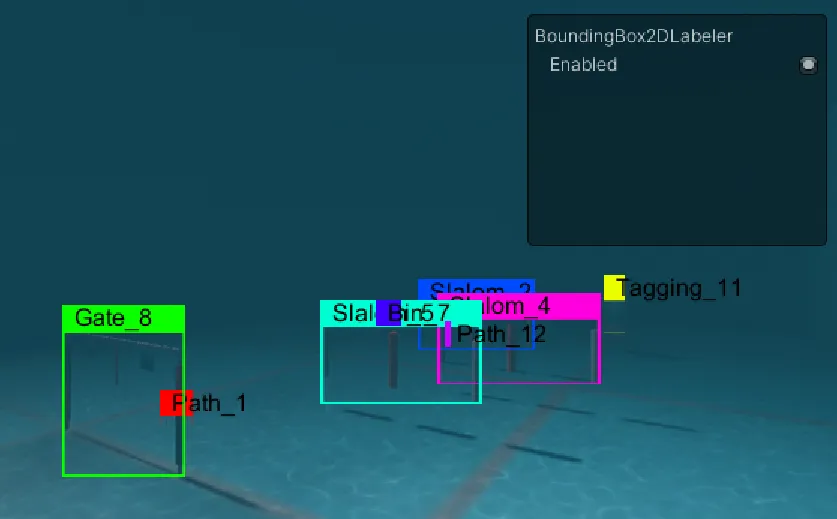

For vision training, we wanted to be able to train computer vision models on competition game elements, even if we did not have the physical elements. This was another direction motivated by Robosub 2024, where we had to spend the first half of the week collecting vision data to train models due to lacking sufficient data beforehand. To obtain synthetic data, we used the Unity game engine to create realistic renderings of game elements underwater. A major upside of this approach was that it was easy to implement and could be easily reconfigured for different lighting settings, water conditions, etc. Additionally, the Unity Perception Package allowed us to the significantly streamline the process of generating large quantities of annotated bounding-box data for use in vision training.

For physical simulation of the robot (e.g. for testing controls and motion), we used the Gazebo Garden simulation suite with its Hydrodynamics plugin to simulate underwater dynamics. Gazebo was chosen due to its significant ROS integration, which allowed us to effectively drop in our existing software stack and immediately test it (with only minimal changes for testing). Although we were not able to finish our simulation component in time to use it before real-life pool tests began, we intend to use it going forward, and are excited for the long-term possibilities that simulation might open up for our software team in the future.

For vision training, we wanted to be able to train computer vision models on competition game elements, even if we did not have the physical elements. This was another direction motivated by Robosub 2024, where we had to spend the first half of the week collecting vision data to train models due to lacking sufficient data beforehand. To obtain synthetic data, we used the Unity game engine to create realistic renderings of game elements underwater. A major upside of this approach was that it was easy to implement and could be easily reconfigured for different lighting settings, water conditions, etc. Additionally, the Unity Perception Package allowed us to the significantly streamline the process of generating large quantities of annotated bounding-box data for use in vision training.

Game element renderings in the Unity game engine